Bash Ortega: Summer Residency

- Aug 10, 2025

- 4 min read

At SMUSH, a brief encounter with an excellent draftsperson and analytical intellect.

SMUSH (340 Summit Ave.) is not a restless place, and its directors are not fickle people. They’ve just got a lot they’d like to get to, and there are only so many days on the calendar. Benedicto Figueroa and Katelyn Halpern need to, er, smush in openings, poetry readings, community meetings, fundraisers, work-in-progress sessions, dance performances, jumpsuit-sewing tutorials, and other events that really can’t be named or even fathomed. An artist cannot hang on these walls for too long. Somebody else is waiting for her turn.

This SMUSH summer has belonged to SMUSH residents, although each residency hasn’t lasted very long. Artist Gabe Chiarello splashed a summer-themed group show all over the place — one featuring work by Erik’s Paper Route, Wendy Fox-Warfileld, Aria Mooney, and sixteen other provocateurs — featuring playful, colorful pieces, many for extremely reasonable prices, that looked like they were made quickly and with great joy in their creation. That was fun. Better still is the takeover by Florida-born, Brooklyn-based Bash Ortega, a talented etcher, printmaker, and draftsperson with the soul of an old-fashioned pointillist. It’s been up for a little less than a fortnight, and today, they’ll be taking it down. Such is the way of summer residencies, and summers in general: blink and you’ll miss the good stuff.

In SMUSH tradition, the product of Bash Ortega’s residency sprawls and flows everywhere it can, including the front window, the gallery-runner’s desk, the bathroom, and, at least when I visited, all over the floor. That’s part of the charm of the artspace. But in this case, it’s a little misleading. On the page, Ortega makes art of considerable precision, with each dot and dash serving a specific illustrative purpose. Sometimes they’re there to establish the outline of an object, and sometimes they’re jottings, added through little finger-flicks, meant to provide shading and contour.

In a typical Ortega piece, the artist will add hundreds of these, usually in black ink, all bunched up like iron filings pulled into order by a magnet. Beyond the parameter of the object Ortega is drawing, however, there’s nothing — not a smudge, not a contextualizing line, no errant marks whatsoever, but instead a white expanse signifying negative space. You aren’t to look there. You’re meant to focus on the same thing that holds Ortega’s concentration.

Usually that’s some sort of gorgeous, terrifying innard. Ortega is interested in the dry latticework that supports organic life. This artist is also a biology student, and one who has been privy to a few dissections. Many of these pieces peel the flesh straight off the skeleton and expose the bone with a ruthlessness — nosiness, really — that only could have come from a scientist.

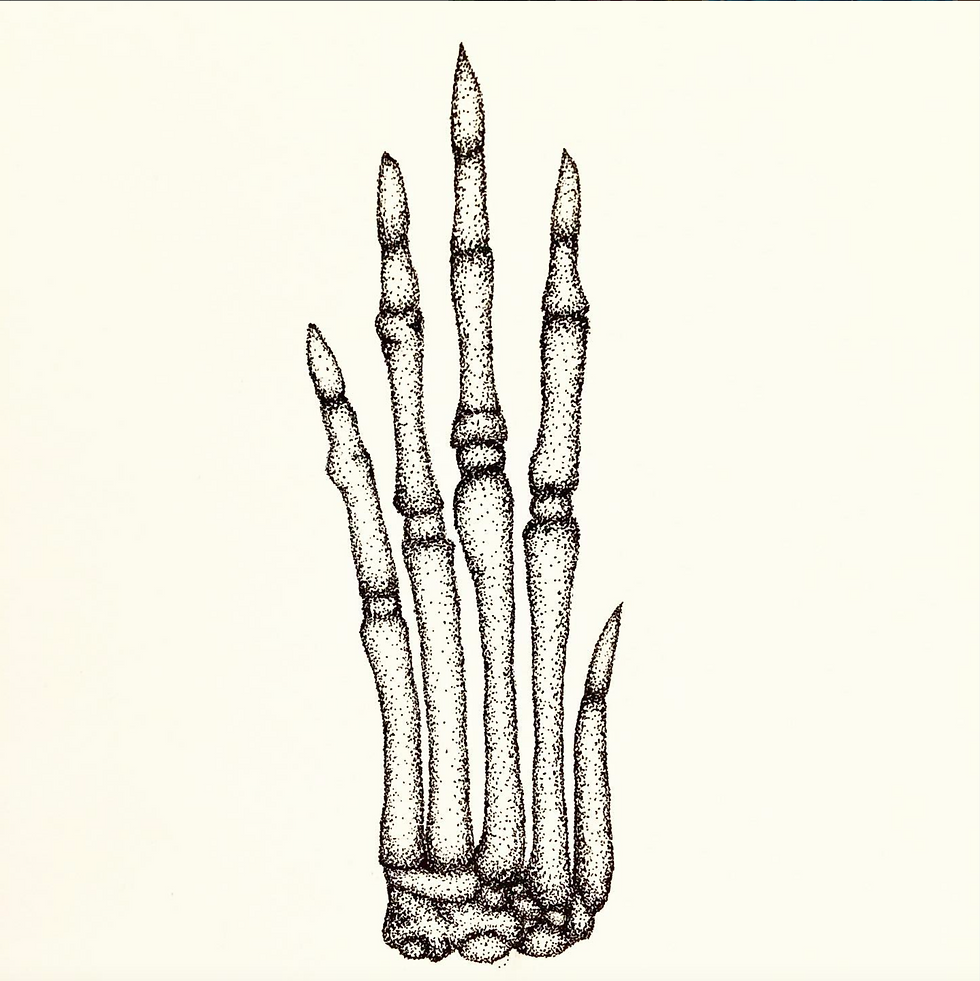

One presents us with the ragged-toothed, jutting lower jaw of an ungulate. Another scrapes the sinew from the long digits of a rabbit’s foot. Still another slips a disc from a spinal column with the deftness of a pickpocket extracting a coin from a purse. These images are pinned and pressed to the page like specimens for examination. Ortega’s treatment of the bone is unsparing: we’re shown every ripple, every pockmark and stratification, every uneven ridge, wobbly joint, and cracked incisor. Only someone fascinated by anatomy, and the firm inner frame that our squishy exteriors disguise, could have summoned the patience to conjure these pictures, out of thousands of dots, with such precision.

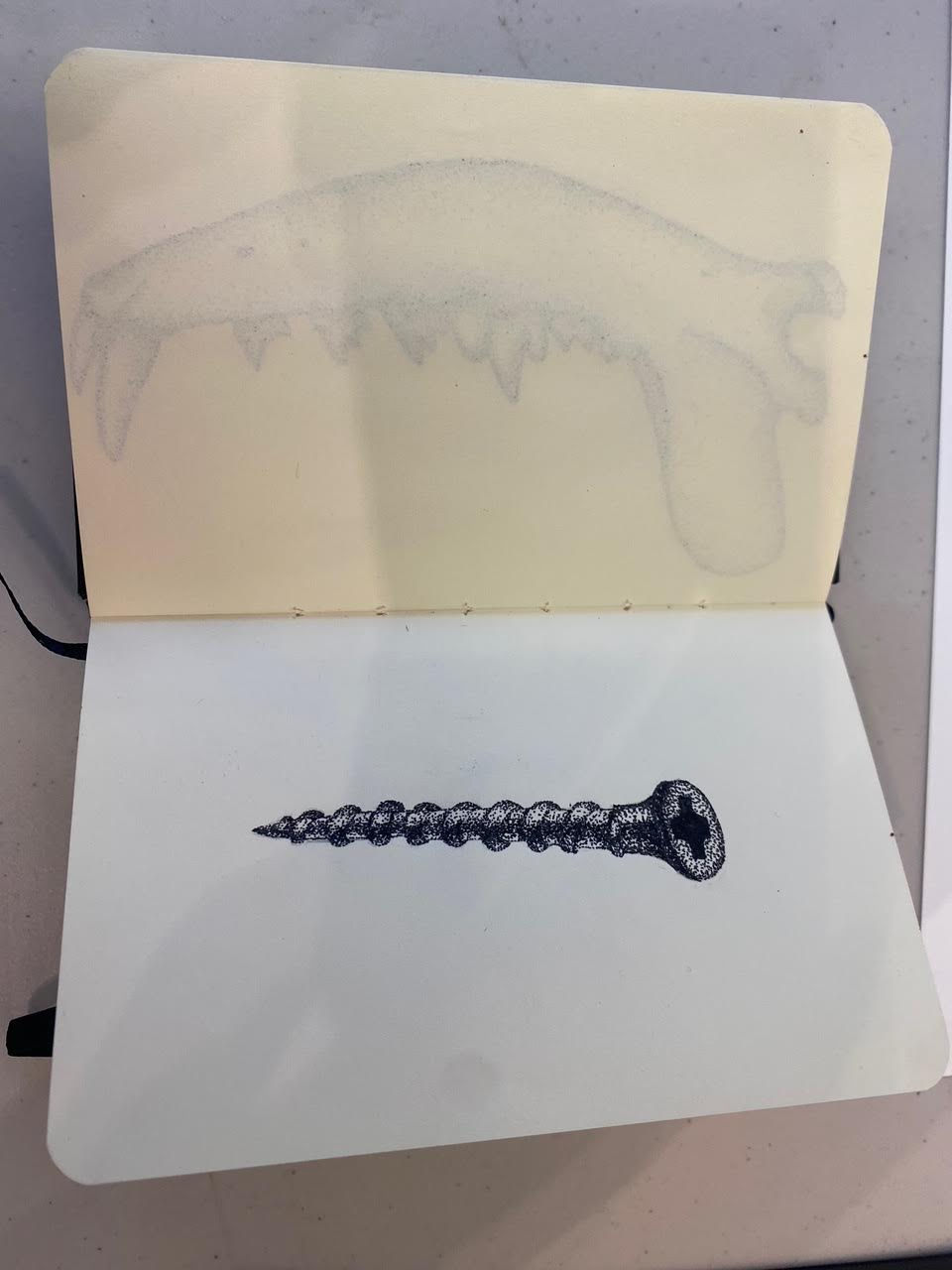

Drawings of inanimate objects, many tucked into sketchbooks, are done with the same obsession with detail, and the same tiny hailstorm of ink ticks. A delicious little portrait of a single screw is a study of the interplay between black marks and white space, and a textbook example of how shades of metallic gray can be implied by varying the frequency of the dots. It’s an illusion, but it’s an extremely persuasive one. Ortega’s hardware means business: these spiral ridges look awfully sharp, and its business end is so pointed and savage that you might worry it’s about to rip straight through the paper.

More dangerous still is Ortega’s image of a railroad spike given heft and a patina of age via orange dots strategically interspersed among the black ones. This rusty customer is a star of the show and it looks like it knows it. Ortega has taken to screening it on to t-shirts. Here in rail-mad New Jersey, I’d expect the artist to find some takers.

The whole residency feels like a quest for the definite: the hard, real, material stuff that gives objects their shape, and the small building blocks that are the cornerstones of anatomy. Ortega’s diagnostic eye is unsatisfied with surfaces. Instead, it’s drawn to the screws and joints that hold the apparatus together. Pointillism becomes a kind of constant probing, an examiner’s mark, testifying to the seriousness of a renderer recording the smallest measurements possible. With skill and sustained attention like Ortega’s, who needs a microscope?

The artist refuses to sentimentalize these bones, or the animals they once were, instead presenting these still remains with the sort of honesty that science professors applaud. The small exception is a fetching, balanced drawing of a wishbone, which, with its cloudy background uncommon in Ortega’s work, whispers a little of mysticism and luck. All of the meat has been pulled from it; it’s desiccated and ready to be tugged. It looks as if it would come apart with a dull snap. And so it does, in our minds, anyway, releasing good fortune from the dried-up marrow, sending us off with a burst of chance — and a parting reminder to the map-maker that nothing is ever settled, no matter how granular our renderings of what we see, no matter how closely we look.

(Yes, the Bash Ortega residency ends today. So does the outstanding Kamonchanok “Bung” Phon-ngam show at the IMUR Gallery. I say you ought to see them both. The distance between Paulus Hook and McGinley Square shouldn’t be an obstacle: it’s going to be a lovely afternoon.)