“ICU/USA”

- Eye Level

- Sep 30, 2025

- 6 min read

Updated: Oct 28, 2025

Forty four photographers keep their eyes on America — even when America is hard to look at.

You’re on edge. Why wouldn’t you be? Masked police are rounding up people on the streets of American cities. Those detained are shipped to private detention centers that exist in a blank zone beyond judicial oversight or regional supervision. This weekend, The Guardian described a CoreCivic prison in the California desert as hell on earth: crowded, unsanitary conditions, dirty water, torture, unconscious inmates denied medication. Shirsho Dashgupta of the Miami Herald reported that more than two-thirds of the men incarcerated in Alligator Alcatraz cannot presently be accounted for. Shortly after delivering a speech that echoed Joseph Goebbels’s rhetoric, Stephen Miller celebrated NSPM-7, a White House directive that criminalizes dissent and empowers federal investigators to lay a dragnet and start the engine. In this febrile environment the President has announced his intention to send the army — the United States armed forces — to Portland, Oregon, treating it as a rebellious province that needs to be subdued.

Are we the next target, or just one among many? ICE is stirring the waters here, separating a father from a child during a traffic stop last week. James Solomon, a Councilman and a leading candidate for mayor, called the raid an abomination. Neighbors did too. Among those objectors were the principals at nearby Eonta Space (34 DeKalb Ave.), a gallery that has made room for works of art that are, according to the new mandates circulated by the White House, a threat to the welfare of the country. Never mind that the spirit of inquiry cultivated by Eonta Space (not to mention their compassion) is widely shared by people in Jersey City. The members of this administration are comfortable slapping the lot of us, Hudson to Hackensack, on their enemies list. Like it or not, we’re all troublemakers now.

And like all good troublemakers, we’re armed with cameras. The forty four photographers of “ICU/USA” turn their lenses toward the public spaces of a place that has lately felt less like a country than a battlefield. Many of the one hundred and twenty shots in the show give the impression that they were snapped fast, on the run, perhaps by people pursued by authorities or shooed off of intersections by police. Though they’re artful, they’re also dutiful and photojournalistic. They were taken to register an impression of the way things are, and chronicle a society undergoing a savage sort of transition. Even from a marginalized position, even pushed from the halls of power and targeted, it is still possible for us see the United States. Whatever our country has become, it cannot be hidden. Acts of erasure will not deceive our eyes or mess with our memories. If the USA is on the verge of consignment to the ICU, we’re going to follow the ambulance until we can’t anymore.

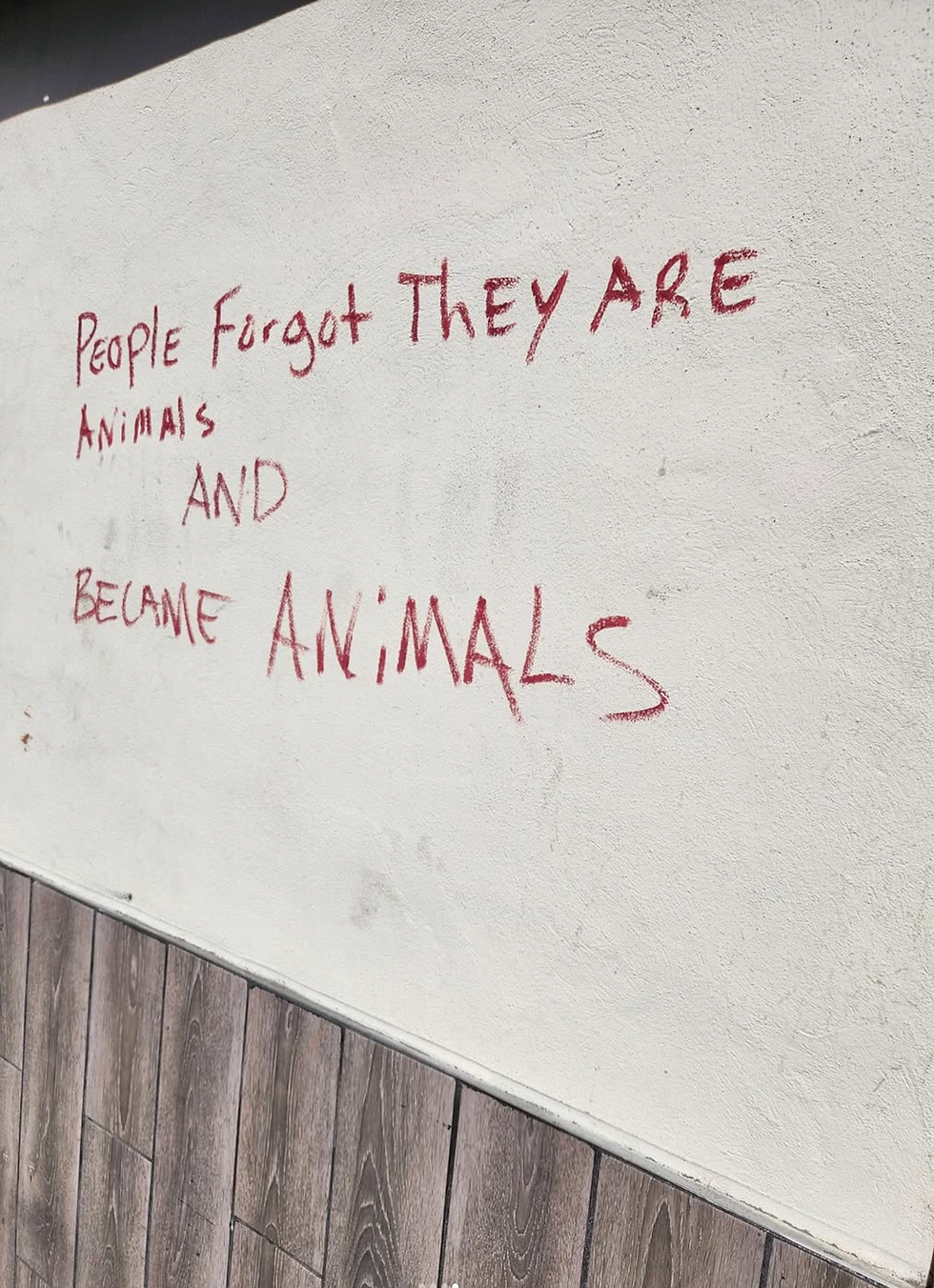

Some of the protests are overt: Ray Schwartz’s images of grimly determined protesters at No Kings rallies, Christine Fischer’s faces of everyday dissidents in the snowy public square, Nanette Reynolds Beachner’s shot of nail-polished fingers lifting a kiss-off sign to the President, Lucy Rovetto’s opinionated bathroom stall, chatty, crude, funny, and clear in the manner of enhanced stall doors across the nation. Schwartz brings us a straight-up reclamation of Newark Avenue by a group of jump-ropers in hazmat orange, surrounded by a crowd gathered beneath the Turnpike extension. Then there are the bodies that have hit the floor, like the black-clad individual in John Kenneth Ramirez’s midday sidewalk shot. The subject has a high-end shopping bag in easy reach and a spray-painted crown from Rick the Ruler promotional graffiti right by their head. The character’s posture, though, is that of a person resigned to a horizontal fate — at least for a while. Adam Pitt catches a supine African-American man at the lip of the Mississippi River, at the very bottom of a series of concrete steps. He might be down for the count, or he might be relaxing, seizing back what is his, by birthright, as a citizen of the U.S.A. and child, as we all are, of the Father of Waters.

As exhausted as these street-sleepers may be, their presence underscores one of the main themes of “ICU/USA.” Just by taking to the road and occupying it, a modern subject is engaged in a political act. Being outdoors means being counted. There’s nothing intrinsically confrontational about Brian Hopkins’s “Tumult of Tubes”: it’s just a shot of a brass band in a park on a glorious day, with light polishing the bells of the horns and everybody bearing his metallic burden with ease. They’re getting ready to march, but for the moment, they’re in no kind of array. Some press their lips against the mouthpieces of tubas, others prepare their game faces, and still others look around, overwhelmed and delighted by the chaos of human activity under the sun and its implicit possibilities.

Frank Hanavan’s experimental “India Square” is similarly busy, but more intense, and more obviously defiant. Hanavan, who has emerged as one of the most talented photographers currently working in Hudson County, makes his ethnic neighborhood shine with pride and a sense of inevitability and self-possession. Every inch of the shot is busy with color and action; this is a restless world, but an attractive one without any wasted space. Brighter than the signs advertising local business are the eyes of a woman pushing a stroller: she looks determined, proprietary, and fiercely at home. Hanavan amplifies the otherworldly quality of the shot by making the bottom of the print a mirror of its brilliant top half — almost as if we’re watching this scene from the front windshield of a new car with a shiny hood. The main character walks through a tunnel of light and color, guiding a child, staking a multigenerational claim to the busy American street.

Like just about everybody in “ICU/USA,” she’s on the move and angling for release. Even Abdul Bassir Miller’s astonishing, reverent black and white photographs of a naked and young African-American “Son of Man” catches this black Jesus-figure in action, in the gloom, hands up and bloody stigmata visible, with a searchlight scouring his bare chest, his chains, and his gold cross. He’s in search of a self-sacrifice that might double as transcendence, but he, like the Christ of the Gospels, is probably about to have a close encounter with the justice system instead. Hints of the lock-up are general across “ICU/USA,” as this show is freighted with images of locks, gates, fences, and closed doors. Jerome China, always a firm hand with a signifier that evokes the slave trade with little room for interpretive ambiguity, wraps an American flag in the sort of chains we expect to see around the feet of human chattel.

Yet most of these barriers, tethers, and grates are old and rusted, scalable, or simply broken and not up to the task of penning anything or anybody in for long. The cloud restrained behind the cyclone fence in Ian Klapper’s clever “Confinement” looks ready to sail away over the bent top of the chain links. Benedicto Figueroa’s photographic entreaty to “Lock the Gates” feels like a desperate hope from a jailer with little faith in the rickety old security system depicted. Marc Fell’s “Rich Man’s House” is easily penetrated by an intruder, and the closed doors of “In Memoriam” give the impression that they can be unsealed by anyone with the faith to grab the angel’s wings that hang on the handles and pull. Most representative of all is Katelyn Halpern’s “An Unlikely Garden,” a post-industrial lot fronted by a wrought iron fence with a rough breach in it. Even in a charmless enclosure, things still grow.

From these images, a view of the U.S.A. as a crumbling carceral state emerges. Yes, there are tall walls and barbed wire; yes, there are institutions put in place to hold the people in check. Yes, we are obsessed with barricades and lines of demarcation. But what we’ve got is not nearly sufficient to the task of restraining the volcanic force of the American populace. The barriers are brittle, the chains are oxidized, and there aren’t many guards at the gate. Systems of domination and oppression feel eternal and unmovable, but that’s only how it looks from the outside. Look harder at the prison walls, and you can see cracks everywhere, Maintenance hasn’t been great, and the authorities, scant when seen, have hidden themselves away in high towers.

This vision may prove prophetic. It is not exactly optimistic. It’s anyone’s guess what forces will be released when the barrier falls. It might be wise if we all took the advice in Diana Dominicci Stewart’s photograph, shot within easy walking distance of that ICE raid. There, some wag has affixed life advice to a stop sign, a one-word would-be national anthem meant for oppressive authorities and angry young men alike: chill.