“Overlap: Life Tapestries”

- Eye Level

- Aug 15, 2025

- 5 min read

A spiky, suspicious, and occasionally uncomfortable group show shakes up Gallery 14C.

Shoes are provocative. The more a shoe is worn, the louder it speaks. A shoe that’s seen some hard travel has been entrusted to shield the tender soles of some vulnerable person as she moves through a hostile world. If we see the shoes and not the person, we’re reminded that the things which once protected that person are no longer there. An empty shoe is a testament to a body in peril. It’s no wonder, then, that empty shoes are used in museum shows so frequently that they’ve become a bit of a cliché.

There is, however, nothing conventional about “Hide,” the footwear sculpture series by Jean Shin. The Brooklyn artist has peeled the bottoms off shoes, extracted the heels, and flattened the leather insteps. Then she's taken the remains, strung them together tightly, and hung them by the score in bunches. The result is to shoes as fruit roll-ups are to strawberries. What they once were is recognizable in what they are, but the brutal conversion process has wrung all of the sentimentality out of them. The poignancy that is so often found in shoe art is missing in Shin’s pieces. Instead, what once was made to fit the body is now unwearable. The converted shoes look like lips agape, caught in an expression of bewilderment after words have failed.

Two “Hide” shoe sculptures presently hang in Gallery 14C (150 Bay St. at the corner of 1st and Provost, 2nd floor), radiating tension, trauma, and plain old trouble. They’re centerpieces of “Overlap: Life Tapestries,” a barbed-wire enclosure of an exhibition filled with discomfort and the residue of peril. Curator Vida Sabbaghi has something to say about the experience of being female, and she’s chosen her participants accordingly. The thirteen women in the show see the body as a battleground — and from the looks of it, they aren’t winning the battle.

Sometimes the perilous fight is made visible. In “Knight at Ease 652,” Linda Stein fashions a bodysuit out of Wonder Woman cartoons, preserving exclamations, explosions, and the sounds of physical combat. Her superhero maintains her famous composure, but she’s beset on all sides, and forced to use her muscle against the adversaries that surround her. Stein hangs this dress in midair and allows its shadow to fall on a faintly outlined Wonder Woman on the gallery wall. It’s unclear if she’s coalescing into heroic being or fading away.

Mostly, though, the violence is heavily implied. In Angela Fraleigh’s gripping painting “Slight,” a pair of women share an embrace that feels more like an attempted rescue. The figure on the top of the painting appears to be saving the one on the bottom from an encroachment of malevolence. Waves of black paint and resin frame their faces, lapping at their cheeks, and threading through their fingers, overwhelming them, constricting them, and binding them together. One of the women has the black stuff up to her lips. She could be coughing it out, or it could be suffocating her. Fraleigh has matched the image to the size of her emotions: this is a big painting, and she means to hit us hard.

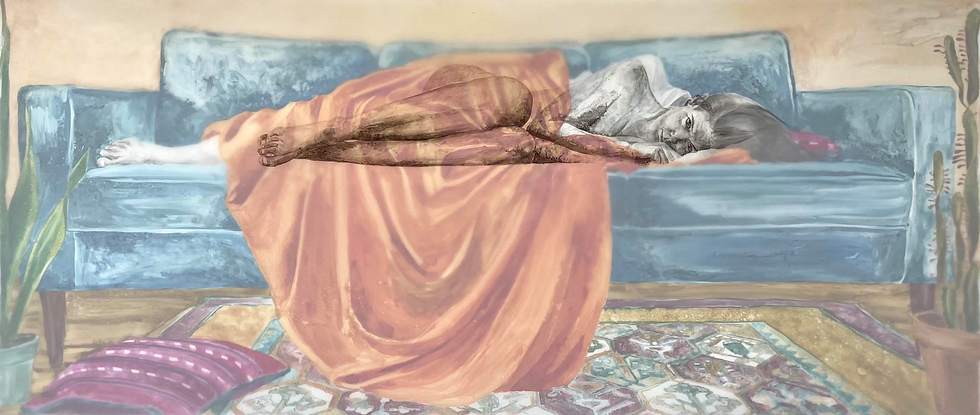

Some of the other paintings whisper, but they’re just as effective, and maybe just as desperate. Alida Wilkinson makes use of the curious translucency of mylar surfaces for “Interior II,” the study of a wary woman in repose. The partially naked subject on a sofa has turned to face us, but her look tells us that she doesn’t trust us. Her forehead is furrowed, her eyebrows are tense, her mouth is unsmiling, and the balled-up hand in front of her chin doesn’t look like it’s there for support alone.

Behind her, eclipsed by her body, there’s another figure. It’s possibly male, and definitely larger than she is — we can see its legs and feet extend well beyond hers. Yet it does not throw an arm or a leg around her. These bodies are as close as bodies can get, but they don’t seem to be interacting. Through the whispering, spectral qualities of mylar and ink, Wilkinson has opened up the possibility that the second figure in the piece isn’t a lover at all, but a shadow, or even a memory.

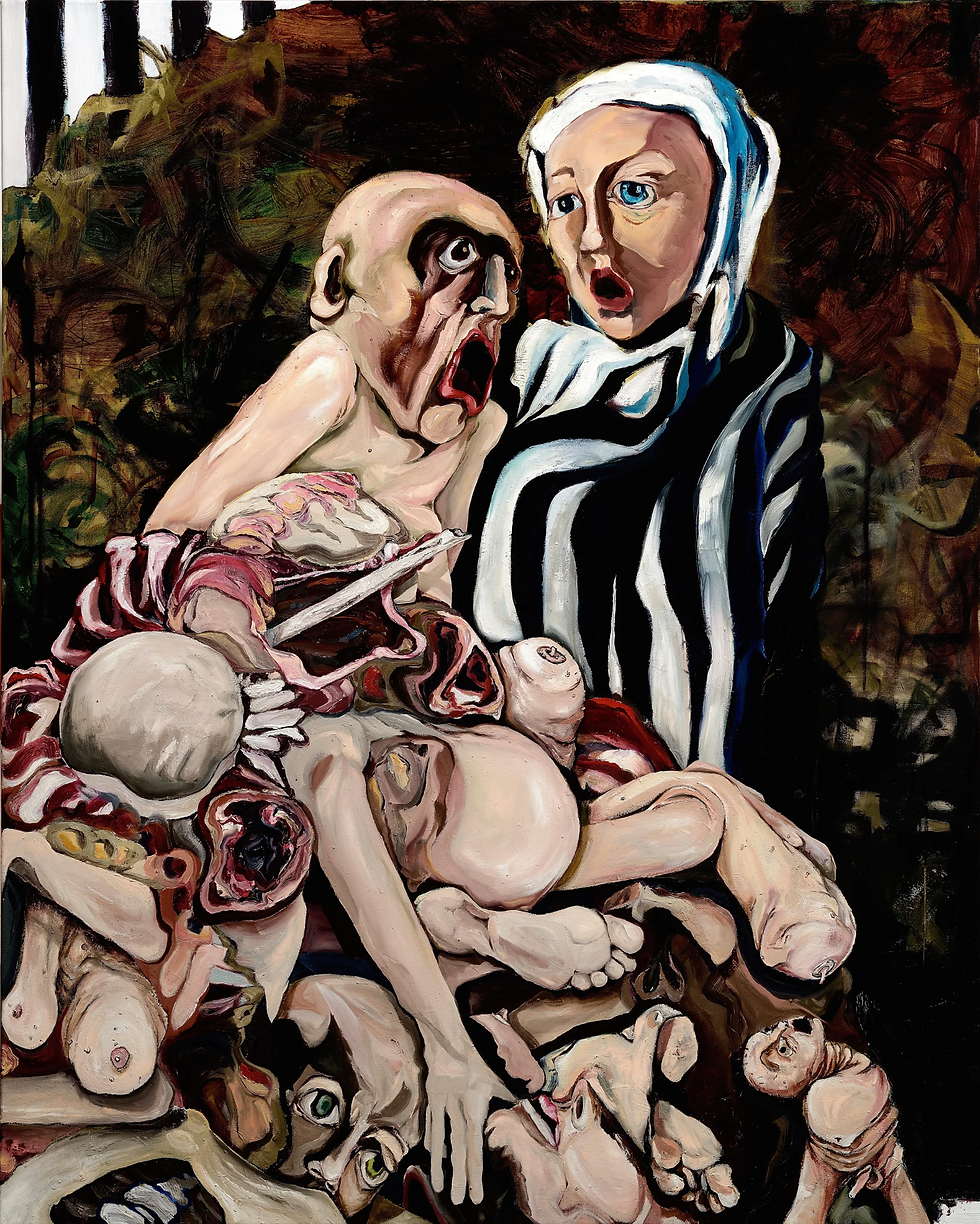

There’s ambiguity in the work of Carrie Alter, too, even as it leads with ferocious discontent. “That Night on Bald Mountain” is pure carnage: a wailing couple in eyesocket-melting horror before a mound of human body parts. The painter renders it all in agonizing detail and copious, blood-tinted fleshtone, including dead babies, the lifeless eyes of chopped-off heads, slumping feet, the torso cavities of the decapitated, and distended, oozing mammaries. We don’t know what happened here or why, but the black and white prison-yard stripes in the background and on the robes of one of the mourners speak of war and internment.

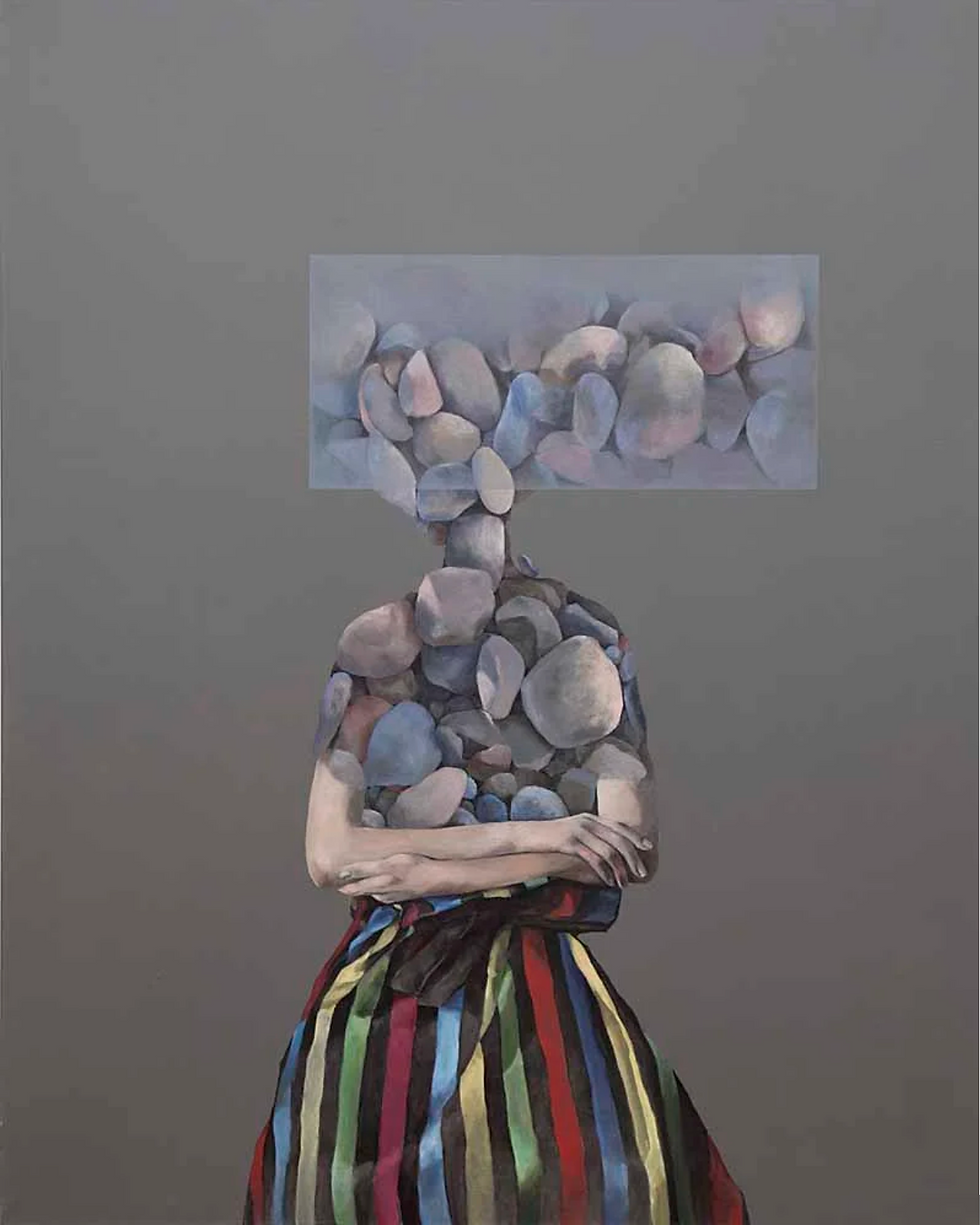

With its huge, bulbous breasts, bent cilia, and peculiar, sickly-yellow patch where its vagina should be, Alter’s headless “Beautiful Grotesque” stalks us straight from the frames of a monster movie. Acrylic painter Shari Weschler’s characters aren’t quite such charismatic abominations, but they don’t have conventional faces, either. The cross-armed protagonist of “Parting Ways” seems pert and attentive in her flaring, striped dress, but her top half is composed entirely of stones.

Then there’s Carla Goldberg’s “Goddess of Hibernation,” a roaring mixed-media piece made from sheets of resin, pigment, and should you look carefully into the center of the maelstrom, a preserved creature. This is the female body as a storm system, all circulating lines and weathered cracks and a surface-level fragility that, upon inspection, turns out to be tougher than steel. Right there in the eye of the hurricane — the womb, as it’s depicted — is a place of shelter for the body’s slumbering charge.

Just like Alter’s “Grotesque,” Goldberg’s “Goddess” bares breasts that do the work we normally associate with eyes. In these portraits, it’s those nipples that stare back at us. All over “Overlap,” faces are hidden, occluded (as in Lola Flash’s photo of a masked woman in hazmat orange on the MTA), fragmented (as in Bri Cirel’s time-slip celebrity oil paintings) or torn away altogether; mouths are clogged; lips are mute. Is this the well-known caricaturist’s trick of leaving the head featureless so that the viewer can identify with the character and feel her predicament?

In part, it is. But it’s also a creeping suspicion among the artists of “Overlap” that our noggins have really ben letting us down. In times of mortal peril, we fall back on the wisdom of the body. Here, the female body is speaking univocally. Stand back, it says, or tiptoe across the battlefield at your own risk.

(Gallery 14C is open on weekends from 1 p.m until 4 p.m. or by appointment. “Overlap” will also be on view during tomorrow’s Downtown Art Crawl. That starts at 2 p.m. tomorrow and lasts until 5 p.m., and also includes the studios at the Project 14C residency at 157 1st St., Deb Sinha’s “Cult of Beauty” at Art House Productions, “Summer Mosaic” at Novado Gallery,” and other participants listed here. I’ll be at the Crawl all day, so do come say hi. I get lonesome.)